The Partner Artisan Communities of Rags2Riches

At Rags2Riches, we make things that matter and weave joy into every story.

Whenever we create a new product, we like to make every detail meaningful. Our designs always feature the signature R2R weave, but wherever we can, we also like to add a special touch. Our collections often include carved wood or indigenous textiles handcrafted with care by a local community. By using high-quality artisanal materials, we can ensure the longevity of our products.

Rags2Riches was built supporting artisans. At first, this only included our very own artisan communities scattered across Metro Manila. As our company grows, we are proud to extend our support to fellow social enterprises within the city and far-flung weaving communities.

Join us in taking a closer look at the artisanal elements we’ve incorporated into our designs at Rags2Riches over time.

Balai Kamay

Balai Kamay is a social enterprise that produces custom wood items. The company employs woodworkers from Tondo (an area in Manila known to be concentrated with the urban poor) to construct whatever the client needs. Mostly, their most notable products are gift boxes and home cabinets. We saw an opportunity to get creative!

Wood, especially something as lightweight as what Balai Kamay offers, allows us to design more structured bags without the use of plastics like polyvinyl chloride (PVC). This little innovation led the way to one of our newer designs, the Kahon! We use wood panels commissioned from Balai Kamay as gussets to our sturdy sling bag.

Rei Tugade founded Balai Kamay in 2016. Having studied business administration, she naturally ventured into the corporate world, helping grow small enterprises. She was in the process of looking for souvenirs for her sibling's wedding when an idea sprung for a potential business venture: woodwork crafts!

To get the company off the ground, Rei maximized the plethora of programs and projects offered by the Department of Trade and Industry: Negosyo Center (Quezon City), Kapatid Mentor Me, Design Center of the Philippines, and their Shared Service Facilities. Balai Kamay has since then become a regular at major fairs such as Sikat Pinoy and Manila FAME.

Weaves

As you can probably guess, we here at Rags2Riches are totally enamored of handwoven fabric! Not only are they beautiful, but the patience, craftsmanship, and time that a weaver puts into practice are what inspires joy in our design.

We are thankful that the Philippines is rich in a weaving heritage, both widely diverse in every region as well as rooted deeply in history. To honor this enduring art form, we’re taking a closer look at these weaves and the cultures that have brought them about! These are a few of the indigenous fabrics that you might find on an R2R Bag:

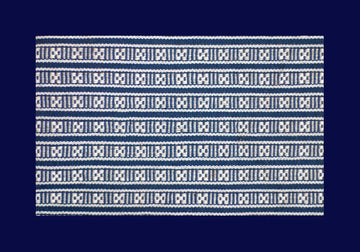

Mangyan Ramit

Mangyan Ramit is a proud product of the Buhid and Hanunuo—two of the eight indigenous groups from Mindoro collectively known as the Mangyan. As seen in the image above, Mangyan Ramit is identified by its intricate geometric patterns. The Hanunuo Mangyan called their weaving process “habilan” and the machine that makes it possible is the “harablon” (backstrap loom).

A backstrap loom is a simple (yet inventive) contraption that is supported on one end by a band that wraps around the weaver's waist and by tying the opposite end of the loom to a beam. The tension is kept taut by the sitting weaver while strapped in.

It can take as long as one week to produce a few feet of Mangyan Ramit. Originally, this process took even longer as the Mangyan also produced their own thread. They cultivated their own cotton trees. They manually “spun”, or beat (in the case of the Hanunuo people), the harvested cotton to fine strands until finally, the threads were dyed with indigo. All of this happened even before a loom is touched. Today, the thread is conveniently sourced in various ways: brand-new from local stores or upcycled from industrial surplus.

Mangyan Ramit is traditionally used by Mangyan women as skirts or as blankets to carry their children. The indigo-dyed Ramit skirts distinguish Hanunuo Mangyan women from others in non-Mangyan communities.

T'nalak

Weaving is not just a practical necessity, in some tribal communities it is a spiritual tradition. Cradled amidst verdant mountains and the calm waters of Lake Sebu in South Cotabato, the women of the T’boli weave with divine inspiration. It is believed that Fu Dalu, the Goddess of Abaca, visits her chosen weavers in their sleep, bringing them visions to recreate on the loom when they wake.

Because of the nature of the fabric’s inspiration, the process is treated with respect and reverence; weavers take care not to step on the fabric, even guarding their own temperament while weaving.

Fu Dalu does not speak to everyone. The distinction of a Dreamweaver is a rare one, even if the quiet town of Lake Sebu is known as “The Land of the Dreamweavers”. Those who do not possess the gift are still free to study and master the craft.

The traditional textile patterns that are woven by the Dreamweavers are what we call T’nalak but the T’boli tribe also weave other pattern variations, which are the ones we use in our pieces.

PhotobyI Travel Philippines(via Wikimedia Commons)

T’boli textile is made of abaca (also known as Manila hemp), a leaf fiber from a species of banana native to the Philippines. The abaca is harvested, combed, and air-dried. Strands are lengthened for weaving by tying fibers together end-to-end. The abaca is then dyed, if needed, with natural extracts from plants. This traditionally resulted in a palette of black, brownish red, and the natural pale color of abaca. Depending on the design, resist-dyeing is applied. Next, the threads are methodically woven together using a backstrap loom. Once completed, the panel of cloth is rinsed in water, flattened by beating with a wooden stick, and finally polished with cowry shells.

It was a long and arduous process that fetched a worthy price. The highest quality of the textile could be traded for carabao or horses. They were used as blankets and clothing but also for wedding dowries and special occasions.

The T’boli started to sell their weaves commercially out of necessity. The weaves are now readily available whether as a piece of fabric or as part of other products. For our Spring/Summer 2013 Collection, we wanted to highlight the T’boli textile with a zigzag pattern alongside the signature R2R weave.

Transition to Northern Luzon Textiles

Venturing north to the highlands, we have Northern Luzon, home to its own diverse array of indigenous groups. Each cultural community has its distinct customs and traditions. As such, weaving styles and traditions across the region are distinctly different.

Rags2Riches sources its weaves from Ilocos, Kalinga, and Ifugao.

The earliest form of weaving in the region was basketry, using knotting and braiding of vegetable fibers such as cane (rattan), nito, and bark (rammie). It is believed that cotton was introduced by Chinese traders as early as the Sung dynasty (960 - 1279). Tribes adopted the raw material and cultivated it for their own use. The local palette for textiles was dictated by ingredients available to make into natural dyes: yellow from yellow ginger, blue from indigo, green from a mixture of the two, red from the bark of the Sappan tree, and so on.

The use of the backstrap loom spread from coastal Ilocos throughout Kalinga, Abra, and Cagayan Valley. Ilocano textiles were widely traded in the highlands. Ilocos, which accounts for a large part of the region, is known for their Inabel (also known by Abel Iloko). The name is generally used for woven cloth from the region as “Abel” means “weave” in Ilocano; “Inabel” means “woven” and “Agab Abel” pertains to loom-weavers.

Maritime trade encouraged the development of textiles in the country. Ilocanos bartered cotton for precious goods such as gold, ceramics, and iron. Abel Iloko was renowned for being so sturdy that it was used as sails. When the Spanish took over the archipelago, they began using Inabel as sails for their own galleon ships and sometimes also as tax payment.

The strength of abel could be attributed to the quality of the cotton used. Our local variety of cotton, “barbadense”, is one of the best in the world; however, due to uncertain trends in its farming, textile producers must resort to other means. Presently, cotton thread is more commonly sourced from Metro Manila or imported from other countries, possibly changing the quality of abel made today.

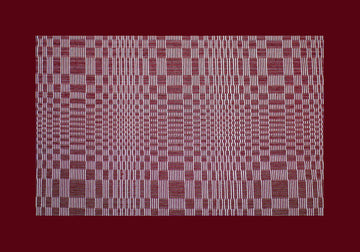

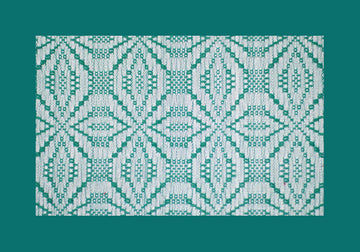

Binakol

Binakol is a specific type of Abel Iloko characterized by a geometric pattern of squares and rectangles. The effect gives an optical illusion of movement as if a circle is radiating or expanding outward. Depending on the dialect spoken or origin of the textile, its name slightly changes: binakol, binakul, binakael, or binakel.

Binakol’s distinct pattern is meant to represent the wind (alipugpog) and the waves (kurikos/kusikos). Other less common motifs are a fan (pinalpal-id) and cat’s pawprint (tinaleb or sinan paddak ti pusa).

Textiles were initially worn by the wealthy and saved for use on special occasions: births, fiestas, and burials. It was believed that spirits could inhabit inanimate objects, like gongs and wooden sculptures; so, textiles like Binakol were given their dizzying designs to trap or ward off evil spirits. Binakol was used as a ceremonial blanket to protect corpses and as a sail on boats to calm the waves.

We’ve used Binakol on numerous occasions, but most notably you will find it on the Casey! We don’t suggest invoking Binakol’s power against bad spirits, but the Casey will probably help turn the heads of a few admirers.

Pinilian

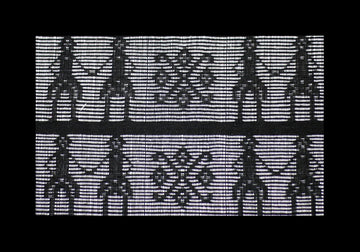

Pinilian is an Abel Iloko characterized by a sophisticated brocade weave. The cloth is made on a pedal loom or pangablan (as called in Ilocano). Sticks are inserted on chosen warp (lengthwise) threads to create designs or patterns that look as if they are "floating" on the surface of the fabric. Red, white, and yellow were the traditional go-to colors of the Pinilian. As seen in the sample above, the motifs largely symbolize humans and our natural environment.

In the town of Pinili, Ilocos Norte they have a technique called "impalagto" that is unique to the locality. Both the warp and weft (crosswise) threads are manipulated for an elaborate pattern.

Making the Pinilian our own, we opt for patterns that are more geometric and decorative (instead of representative). We have repeatedly used Pinilian for the Buslo, our very own and very popular hobo bag!

Binetwagan

Binetwagan is another type of Inabel from Ilocos. As mentioned, historically, weaves hailing from Ilocos were used as sails for the galleon ships during the Spanish Era because of its durability. They were also used as tributes like gold as it was considered at par with the brocade textile of Europe back then.

One interesting fact of Abel Iloko weaves is that they were used by the Ilokanos to communicate safely to one another during the colonization period. They did this by passing on the embroidered designs of the cloth from one town to the next.

Kundiman

Kundiman is another specific type of Abel Iloko, this time defined by fine and subtle patterns; including smaller diamonds within diamonds, waves, and other geometric shapes. As a result of its more subdued design, it may sometimes appear as a plain, yet still patterned, blanket.

Its name, Kundiman, is actually the genre of a traditional genre of Filipino love songs and serenades; with gentle rhythms yet dramatic intervals. Therefore, Kundiman textiles are traditionally given as gifts to couples, newlyweds, or families. The woven threads of the fabric are said to symbolize the bonds of a couple, and the family they will eventually have together.

Kantarines

Kantarines fabrics are handwoven with a loom in the Abra region. They are characterized by their striped design, often coming in varying widths, colors, and combinations. It’s considered an everyday textile.

The fabric is said to have gotten its name from the weavers tradition of singing (kanta) as they create it. No wonder it’s so colorful and so elegant! The textile itself is woven with so much care and so much joy.

We’ve used Kantarines textiles on several of our products, including the 4-Way Top, the Kamara Bags, and our R2R Living pieces!

Ikat

Ikat is a fabric that has been found all over Asia and beyond—across Central and South America. Evidence supports that Ikat circulated through maritime trade as well as developed independently in several locations. Within the Philippines, Ikat may be found in the Ifugao province.

Ikat is known best for its resist dyeing technique. The desired pattern is drawn on the warp and/or weft yarns; the strands are bundled, tightly wrapped together, then dyed as desired; then finally, threads are realigned on the loom and woven together into a finished product.

Ikat is naturally a challenging technique because the threads are dyed before they are set into the loom. Unless every step is replicated perfectly, this means that no two weaves can ever be truly identical. The cloth is either a Warp Ikat, Weft Ikat, or Double Ikat depending on which threads are dyed. A Weft Ikat is more tricky to do as the pattern is not set in the warp, the final pattern only truly forms as the weft is woven into the fabric.

Our little protip for you: one way you can determine genuine Ikat is if the pattern shows through the back in the same way as the front. Real Ikat is identical on both sides since the design is dyed into each thread instead of stamped or printed on. You can get a closer look at Ikat fabric on our special edition Buslo!

Ilaglis

Ilaglis is a type of weave used by the indigenous Kalinga people of the Cordilleras Region for their “ka-in” or “tapis”—wrap-around skirts. The textile is made using Ifugao Ikat, a style of hand-weaving that involves resist dyeing.

Weavers draw their pattern inspirations from nature. Traditionally, the colors indigo and red symbolize the sky and the ground, respectively; mountains are embroidered into the fabric in yellow. Other symbols include the figure of the man, his spear, or a snake. Beading is also a common feature in Kalinga textiles. Adorning your ka-in or tapis with shells or mother-of-pearl platelets are considered a symbol of wealth in the landlocked region.

Members of different tribes in the region identified themselves through the distinct designs of their textiles. The Kalinga community lives on the eastern side of the Cordillera mountain range. They are considered the “Peacocks of the North” for their elaborate dress, personal ornamentation, and tattoos.

The Casey uses Ilaglis in tandem with Binakol and the signature in-house weave. We've modified the color combinations of the Ilaglis to suit a versatile and modern design.